What to Do to Protect Yourself When Making Purchases At Auctions

Some Thoughts Concerning The Henry Bright Album's Photogenic Drawings

On The Economy

Calling It "The Final Installment", Sotheby's Schedules Jammes Part 4 Sale For Paris On November 15, 2008

Photo News Briefs

Updates On I Photo Central Website

Photo Books: Coming of Rage; Dancing Walls; Vernacular to The Masters; and Two Historical Dutch Volumes

Auction to Benefit The Photo Review

The "Quillan" photography sale at Sotheby's New York last Spring was highly controversial in many ways, some of which were noted in Stephen Perloff's earlier article in our July 24th issue of the E-Photo Newsletter.

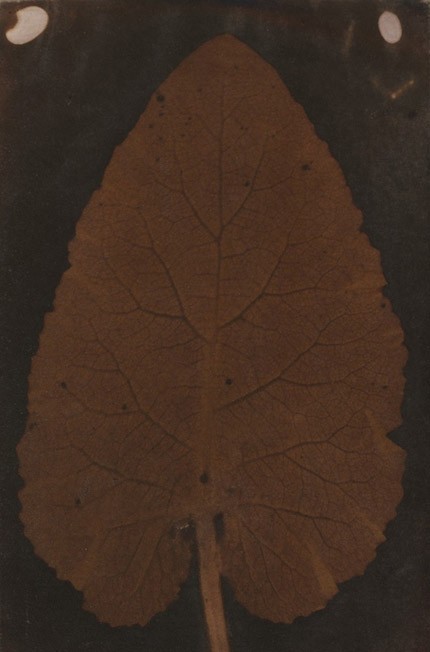

Controversial leaf

One of the most controversial items in the sale was lot 43, the highly debated 19th-century "Leaf", which was reportedly attributed first to William Henry Fox Talbot, and then later in an essay by academic Larry Schaaf to possibly either Thomas Wedgwood or James Watts. You can imagine the joy of Sotheby's and its PR machine at getting this information and being able to hype the price of this object, which in 1989 sold for under a thousand dollars ($900.90 to be precise) by the same auction house to New York photography dealer Hans P. Kraus, Jr. At this earlier auction in London, Kraus reportedly bought six photograms in all out of a mixed album of 24 images. The album was dated 1869 by its original owner, reportedly English watercolorist Henry Bright.

"The range is pretty wide," Sotheby's Denise Bethel told several reporters. "When we thought it was Talbot, we gave it a $100,000 to $150,000 estimate. Now with this other possibility…it's certainly far more valuable." So much so that Sotheby's put a "Price on Request" notation on the lot, which has never been used in the last ten years or so for anything under seven figures in value in the photography area.

Sotheby's Denise Bethel also told the press that Sotheby's, in reevaluating the photo, was relying on the expertise of Larry J. Schaaf, a leading photo historian and Talbot expert. She said Schaaf based his hypothesis on the "W" inscription; the photo's connection to the Bright family; and the fact that it doesn't resemble a Talbot.

But Schaaf was hardly explicit about the attribution, using very vague--but at the same time encouraging--language even in follow-up interviews, like the one when he was interviewed by the New York Times, where he stated: "The reason that I got so excited about this was that it was the most solid, indicative collection I've seen. I'm fully prepared for 'The Leaf' to have been made by Henry Bright, or by his father, after the 1790s. But I've never seen a story that fits together so neatly."

All this was certainly very interesting but doesn't tell the whole story (which is hardly neat at all), nor does it explain how Sotheby's could ascribe such a high valuation to such a potentially historical print on as slim a description as a "possibility", as Bethel herself called it, without further extensive research.

There was considerable disagreement by much of the photo history community with Larry Schaaf on this matter. While I respect him, his rationale that this print could have been made by Watts or Wedgwood (or, as a throw-away: Sir Humphry Davy) seemed to be based on the most meager of arguments. Basically Schaaf, as noted by Bethel, argued that because there was an inked 'W' on the print and some members of the Bright family perhaps once knew the Wedgwood and Watts families (although no actual proof of a meeting or a specific relationship with Thomas Wedgwood by any member of the Bright family was ever made), that it follows that these prints could be the lost precursors of photography. This slender "evidence" of such an important historical matter seemed to many in the field to be research by innuendo, and the context in which it was presented (as a selling tool with no peer review) appeared to do a disservice to both the history of photography, Larry Schaaf's own fine reputation as a photo historian, and even Sotheby's New York expert group's usually good repute as the most knowledgeable auction house about 19th-century photography.

Schaaf's further connection with the former owner and dealer Hans Kraus, Jr. also lent some concern as to his sense of balance on these prints. Besides his purely academic work, Schaaf works for Kraus and usually researches and writes most of his catalogue information. They also work very closely together on other elements of English photography. This is a financial connection not noted by Sotheby's or its PR department, nor by the general press. And, while I don't really think that was the reason for Schaaf's essay, I do think the lack of transparency gives the situation an even more tawdry appearance than necessary. Schaaf did point out to me that he was not paid by anyone to write this essay, and wrote it to merely insure that nothing happened to what he considered to be a valuable and fragile historical artifact, even if of unidentified authorship.

As noted earlier, Schaaf, when interviewed in the New York Times, stated: "I'm fully prepared for 'The Leaf' to have been made by Henry Bright, or by his father, after the 1790s." In fact, Schaaf later told me that he strongly urged the auction house and consignor to pull the leaf from auction in order to do further research, but the consignor was apparently initially resistant to this idea. At the very least Schaaf was more forthright about the distinct possibility that this lot might not be as important a piece as the Sotheby's PR mill was making it out to be. Sotheby's sought and received coverage for this photogram not only in the New York Times, U.S.A.Today and many other major U.S. newspapers and magazines, but also in international publications such as Paris' leading newspaper, Le Monde. To say overstatement was the axiom of the day is, in fact, to understate.

Let's look at some of the quick question marks that set off the photo history community. For example, I have personally owned what is probably one of the earliest photographic images on paper, probably an example of Talbot's early experiments from Geneva that he made in 1834. These were considered to be the first images produced photographically and fixed. This cliché-verre (a print made by placing photographic paper beneath a smoked glass plate on which a design has been scratched) was barely discernable and could only be seen from a raking angle. Understand that this print was actually salt fixed, unlike the Wedgwood or Watts experiments that had no fixing at all. Wedgwood himself noted that his images faded completely from view. So how then were these very striking, dark and dramatic plant photograms by Wedgwood or some other precursor to photography, such as Watts or Davy? How had they survived with such strength of image after over 200 years, when their proposed creators noted that the images they made faded disappointingly after a few hours, despite some unsubstantiated statements by Samuel Highley in the 19th-century to the contrary? (In the next article, Talbot expert Michael Gray poses virtually the same question, as have numerous others. He also poses several other rather devastating questions and their answers.)

More to the point, when this group of plant photograms were sold by Sotheby's in 1984 for such small amounts, Sotheby's experts then noted that the 'W' was an 'N', and was similar to a mark made by Talbot partner and fellow photographer Nicolaas Henneman to indicate which side of the paper was pre-sensitized. The catalogue dated the prints then to "1840-45", although a number of auction observers at the time thought that the prints were actually made later by a much more amateurish method. It was still a little strange that Sotheby's made no reference to its own earlier 1984 catalogue description and that there was now another interpretation of the inked letter on these prints.

In addition, Schaaf's linking the Bright family to Thomas Wedgwood seems to have more in common to the pop culture game of six degrees of Kevin Bacon than true research that would link Wedgwood directly to the Bright album images, as Michael Gray's article points out.

In my own opinion, just from some quick observations, the prints are likely to be from a period somewhere between the 1840s and 1860s. Michael Gray's article even provides some intriguing information that the creation date of these photograms is more likely to have been at the tail end of this period. The Bright album was apparently put together in 1869 and contained a number of images of known dates from about the mid-1840s to the 1860s (although one cliché-verre now attributed by Schaaf to John Herschel was said by Schaaf to be from 1839, but no further reference or evidence of this was provided in his essay). If the Henneman notation is correct, then perhaps they could have been made by one of Talbot's relatives or friends, although even that may be in question, according to Gray; and Schaaf himself now says, that "this leaf, and its companions, do not fit into the corpus of known works by Talbot and his circle."

It is also virtually impossible, according to the evidence that Gray lays out, that this print could be by Wedgwood, Watts or Davies. Thus the value is considerably less than implied by Sotheby's in its publicity or catalogue. An anonymous amateur photogram (or one produced by a Bright family member) from the 1850s-1860s might not be that much more valuable than what Hans Kraus paid for it in 1989; even if one were to put a zero on the end of that figure, you would still be only looking at a little over $9,000. If by a member of the "School of Talbot", the photogram might be in mid-five figures, but certainly not in the seven figures that was implied by Sotheby's by its "Price on Request" notation or the words of its own photography expert to the press.

After numerous top photo historians and academics began questioning the Schaaf essay and Sotheby's attempts at tying this image to pre-photo history, Sotheby's knew it had a major problem on its hands. A belated attempt was apparently made to get the Getty Museum to test one of its images from the Henry Bright album, but the equipment to do this was in transit to Europe when the call was finally made just days before the auction. Plans are still in the works for testing of prints from the album at the Getty, although they have been delayed because of "equipment problems" that were suffered on the trip back from Europe. We will be bringing you the results of these tests after they have been completed. However, many top conservators do not feel that such testing could be definitive, although perhaps a fixing agent of some sort might be detected to indicate that the print was made later, well into the 19th century instead of made at the tail end of the 18th century. Also, testing for the sizing agent might provide more evidence for dating the object, as noted in Gray's article below. It appears to be more likely though that such testing can rule out an early date rather than substantiate it.

On April 2nd, just five days before the auction and after much questioning by the photo history community, Sotheby's decided to pull the lot. Here's how Denise Bethel described the situation in a press release sent out to the media: "Following the publication of the catalogue for the sale of The Quillan Collection, scholars across the field of photography have entered into a spirited and lively dialogue about the possible origins for the "Leaf". Dr. Larry Schaaf’s essay, which comprised our copy for the lot, has inspired and attracted much discourse. This conversation has revealed new areas of research, which will be explored in the coming months. While we had hoped to present the Leaf at auction in the context of The Quillan Collection, a carefully curated group of photographs, the possibility of a definitive conclusion regarding this early photogenic drawing is even more exciting."

Well, perhaps, or perhaps not, depending on your definition of "more exciting". In the following article by Talbot expert Michael Gray, he sets out some very "definitive conclusions" that clearly rule out this print being made by Wedgwood, who died in 1805, or Watts, who died in 1819. He further questions any connection to Talbot.

One wonders why such basic research wasn't done by Sotheby's for what was being billed--or certainly heavily implied--as a photo history milestone before publishing such flimsy justification for a price-boosting attribution, at least by implication. While research is difficult for any auction house, when an implied seven-figure price tag and the rewriting of photo history hangs in the balance on what appears to me and others to be just guesswork, I think some better due diligence would have been in order.

In my opinion this event reveals once again the weakness of the auction system in vetting controversial material under the duel pressures of time and financing. The safer track might have been to publicize the item as an anonymous photogram, date unknown, although I suppose the auction house can claim that it did just that with all the disclaimers popping up in the Schaaf essay and the way Sotheby's carefully wrote up the entry for lot 43. But when the auction house also claims in its publicity, etc. that this "might" be something of crucial and unique historical importance, and handles it as it were, I think it has a duty to take a bit more care than it did here on the research--or lack thereof.

While this article has singled out one auction house, I would be remiss not to point out that Sotheby's is no more culpable than any of the other auction houses in addressing issues of authenticity and proper dating. In fact, in my opinion, Sotheby's usually brings more expertise and care than most of the others to these issues, and in this case even sought additional outside help and ultimately pulled the print (although its future still remains a bit of a mystery). That's the scary part. It's just that I feel the PR hype got a little away from Sotheby's; it and Larry Schaaf were both also saying one thing (no attribution, no dating of the object) and implying something else (that it was an item of historical importance and that there was evidence that Thomas Wedgwood was the creator); and that, coupled to the fact that all auction houses don't currently provide any substantive backstops or guarantees when they make very human mistakes in their listings, gave one pause here. That's not to say that Sotheby's actually made a mistake in its very carefully worded entry here.

Because of the controversial nature of this issue, I would be happy to add and publish responsible comments and responses to these articles in this newsletter as an online follow-up. Such responses may be subject to editing for length and grammar.

Novak has over 48 years experience in the photography-collecting arena. He is a long-time member and formally board member of the Daguerreian Society, and, when it was still functioning, he was a member of the American Photographic Historical Society (APHS). He organized the 2016 19th-century Photography Show and Conference for the Daguerreian Society. He is also a long-time member of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers, or AIPAD. Novak has been a member of the board of the nonprofit Photo Review, which publishes both the Photo Review and the Photograph Collector, and is currently on the Photo Review's advisory board. He was a founding member of the Getty Museum Photography Council. He is author of French 19th-Century Master Photographers: Life into Art.

Novak has had photography articles and columns published in several newspapers, the American Photographic Historical Society newsletter, the Photograph Collector and the Daguerreian Society newsletter. He writes and publishes the E-Photo Newsletter, the largest circulation newsletter in the field. Novak is also president and owner of Contemporary Works/Vintage Works, a private photography dealer, which sells by appointment and has sold at exhibit shows, such as AIPAD New York and Miami, Art Chicago, Classic Photography LA, Photo LA, Paris Photo, The 19th-century Photography Show, Art Miami, etc.

What to Do to Protect Yourself When Making Purchases At Auctions

Some Thoughts Concerning The Henry Bright Album's Photogenic Drawings

On The Economy

Calling It "The Final Installment", Sotheby's Schedules Jammes Part 4 Sale For Paris On November 15, 2008

Photo News Briefs

Updates On I Photo Central Website

Photo Books: Coming of Rage; Dancing Walls; Vernacular to The Masters; and Two Historical Dutch Volumes

Auction to Benefit The Photo Review

Share This